Written by: HİCRAN CENGİZ

Translation: Sebla Küçük

The Turkish army launched a military operation in September 2015 in Suriçi district in Diyarbakır, the center of Turkey’s Kurdish population. The whole area was completely evacuated due to the conflict, which also caused civilian casualties. The process, which took a toll on people’s daily lives, also destroyed the historic fabric of Sur. The fortress and Hevsel gardens, which were inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List on July 4, 2015, immediately before the onset of the fighting. These monuments could not be repaired from the damage that occurred during the conflict. Furthermore, more damage was inflicted upon the monuments during the repairs.

Many questions emerged at the very beginning of the reparation process. After the demolition works, what happened to the excavated materials, which primarily contained locally produced basalt bricks? How much earthwork was excavated and where was it moved to? Were the institutions and individuals leading the transportation work aware of the special circumstances of the area? Were the registered historical buildings preserved in their original condition during the reconstruction process? Were issues related to housing needs and compensation of losses of the residents addressed?

These issues were unresolved during the repairs as the restrictions and fighting still continued. Finally, residents and NGOs held a press statement at the historical Four-Pillared Minaret, one of the landmarks in the city, and demanded “an end to the conflict and protection of cultural heritage.” The statement highlighted the need to stop the damage inflicted upon cultural assets. However, Tahir Elçi, Head of Diyarbakır Bar Association, who read out the statement, was killed during the meeting.

SUR WITH A NEW FACE: URBAN DESTRUCTION PROJECT

The “conservation development plan for Suriçi area” soon turned into an urban destruction project with the conflict. Urban Planner Dilan Kaya Taşdelen gives us an insight about the story of the development plans, which started in 2012, and their impact on the social memory. Taşdelen emphasizes some authentic aspects of Suriçi: “Firstly, the settlement in this city has a very long history. The first settlement area inside the walls was later turned into Hevsel, and these settlements, which hosted numerous civilizations, have survived until today. Secondly, the residents of Sur are actually being displaced for the second time. Field work by civil society organizations and official records demonstrate that people started moving from Sur to Yenişehir in 1950s. The second wave of displacement happened when villages were evacuated in 1990s, and residents of those villages moved to Sur and created the social and economic norms of urban life here.”

Taşdelen says there are rumors that there are families who received some payment, but the landlords whose houses were delivered are now planning to sell their property because the development plans have made the area inhabitable for them: “In the plans, the authentic streets like Yenikapı, where the historical fabric has been conserved very well, will be turned into commercial areas. The buildings in these areas will not be handed over to their former owners. Because these areas are commercial lots, you can’t buy these buildings even if you pay their price. So, in the new development plan, residents of Sur will not be able to go back to their living spaces.”

URBAN PLAN BASED ON “SECURITY”

After the fighting ended in Suriçi, the Cabinet of Ministers passed a decision to “urgently nationalize” the immovables in the area on March 21, 2016. The decision covered 82 percent of the total area inside the city walls. The remaining 18 percent was expropriated in the scope of the previous urban development projects. That is, the whole area inside the walls have been expropriated.

Dilan Kaya Taşdelen emphasizes that 6 areas were labeled as police station zones in the first revision of the plan. Local branch of the Chamber of Urban Planners filed a lawsuit against Ministry of Environment and Urbanization, arguing that “the decision may destroy the fabric of the streets in Suriçi” but the court ruled in favor of the plan “because their priority was security.” Taşdelen says the new development plan focuses on security – she argues that the location of checkpoints in the area were specified even before the development plan was finalized: “It is clear that they are turning the protected urban area in Sur into a tourism hub because the balance between commercial and residential areas or the description of functions of buildings demonstrate that the new life here will not be dominated by residential areas. The plan reveals an intention to create an area that turns into a ghost town after working hours. We see that the efforts in Suriçi instrumentalize the urban plans for potential conflicts instead of focusing on resolution of the problems and conflict. Indeed, urban plans can be an instrument to ensure social peace by upholding social justice or interests of the city; however, in cases like Sur, development plans are being used by the government to protect its own territory and to create new gains in the event of potential conflicts.”

As the displacement in Suriçi continues in a way that prohibits residents from resuming their lives in the same neighborhoods, Taşdelen says the physical structure and economic value of the new buildings and the resulting human fabric they create destroy all footholds that the displaced groups could find here. The people who are the main carriers of culture in Suriçi are kicked out – what remains is an unauthentic area for tourism.

PROTECTED HISTORIC BUILDINGS DEMOLISHED

The conflict zone in Suriçi was later turned into restricted area, which resulted in more damage in the district. Experts from professional organizations, such as Union of Chambers of Turkish Engineers and Architects, or officials from Sur Municipality were not allowed to enter the area. What seemed like earthworks was actually an excavation that exposed archeological layers of the ground. In other words, the historical artifacts underground and the urban memory above the ground were destroyed alike.

A significant number of historical buildings that are under protection or are worthy of protection were taken down during the regeneration process, and in many cases the bureaucratic procedures were not followed. “When the teams from TMMOB entered the area in 2020, they visually analyzed 30-40 buildings that were under protection. For example, the Paşa Hamamı, a historical public bath, was renovated but the parcel borders were not preserved. The stores and adjacent courtyard of the building were swallowed by the road. This can’t be considered as a conservation project because only the main building of the bath has been conserved. The same applies for many other monuments in the area. A building under protection should be conserved with its parcel borders and its relationship to surrounding buildings. In urban areas under protection, a building should be considered to be worth protection for its unique contribution to the fabric of the street even if it’s not recognized as a landmark. But these buildings were damaged during the regeneration process in Sur.”

According to data published by the local office of the Chamber of Architects, 4,985 buildings were damaged in Sur. All buildings were demolished in six neighborhoods which were subject to urgent expropriation, and they were replaced by 500 residential and 200 commercial buildings. 5,440 families left Sur during the clashes that erupted after Turkish military launched an operation in the area against PKK-backed militia who dug trenches to claim control of territory. Approximately 30,000 people moved to other parts of the city, hoping they would be able to return to Sur one day. However, the number of new houses built in the area is not enough even for 10 percent of the families who used to live there.

Nevin Soylukaya, a former official at Diyarbakır Museum who was the head of the Cultural Landscape of Diyarbakır Fortress and Hevsel Gardens, says they compared cadastral maps with satellite images and identified almost 1,800 buildings were taken down. She adds that approximately 100 environmental structures and 40 historical buildings under protection were demolished.

DESTRUCTION OF HISTORY AND CREATION OF “FAKE HISTORY”: AVNİ BEY KONAĞI

As people started moving back to Sur, former residents were shocked by how the buildings they left behind had changed or even disappeared. This process of destruction of a city and its residents was followed by the creation of “fake history.” In an attempt to delete the memory of the city, the new buildings were introduced with a “fake historical background”.

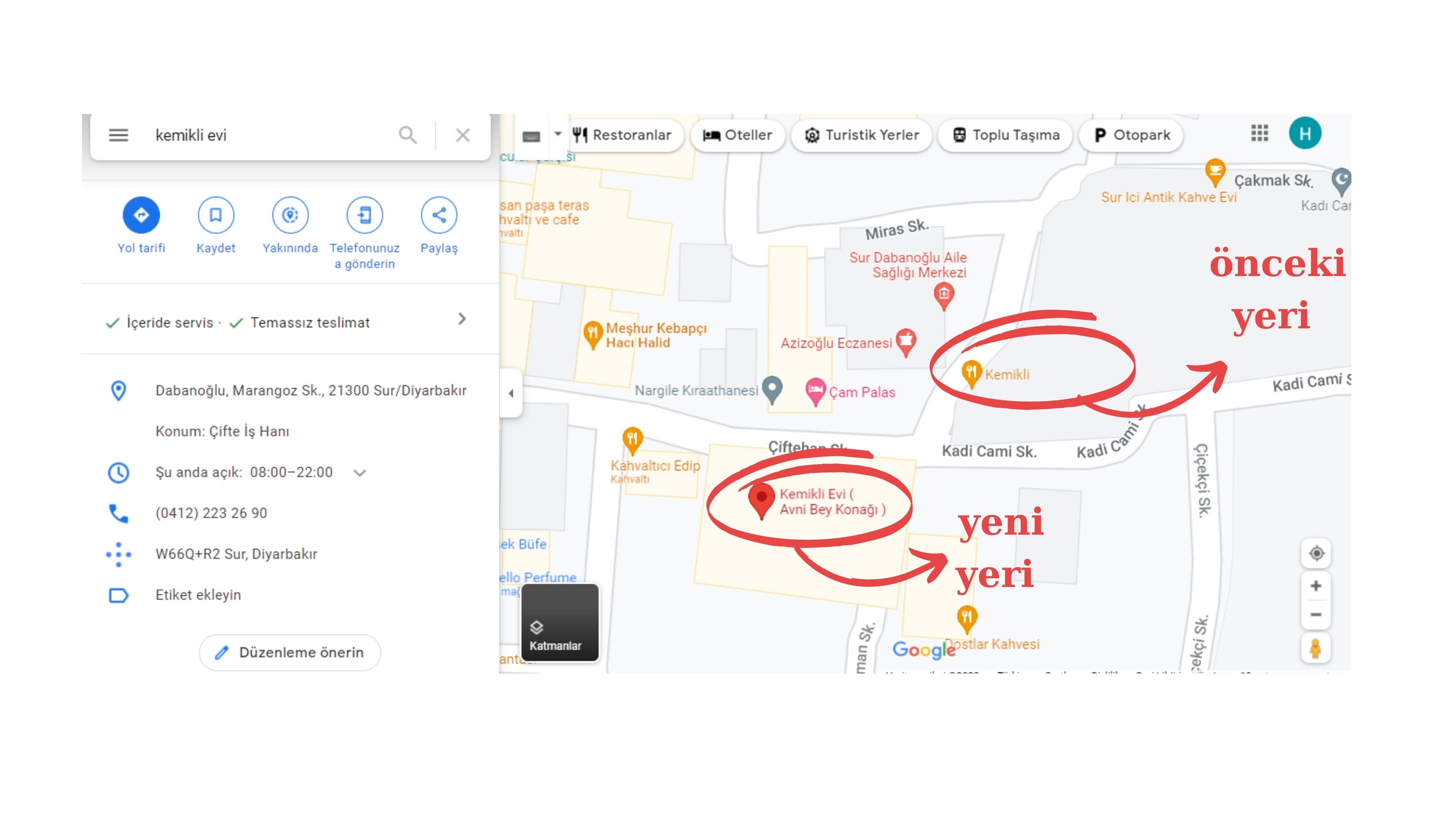

An example of this is the “Kemikli Evi” (House of Kemikli), which is located outside the conflict zone. Before the regeneration project, there was a community clinic at the same location. Taşdelen says the clinic was taken down and replaced with a new structure called “Avni Bey Konağı” (Avni Bey’s Mansion), which was built with the bricks collected from the earthworks: “It was replaced by this new business called ‘Avni Bey Konağı.’ People wonder who Avni Bey is. The local shop owners know he is the father of the owners of ‘Kemikli Evi’. This is a huge problem because an illegal structure in the neighborhood is manipulating the urban memory.”

The opening of Avni Bey Konağı was widely covered by national media, with headlines that read “Kemikli Evi starts offering services in the historical atmosphere of Sur.” These reports claimed the business was established in 1955, and that the historical building dated back to 1850.

NOT ANYTHING LIKE TOLEDO

The authentic houses in Diyarbakır were series of buildings made of basalt bricks, with courtyards shared with neighboring houses. These houses with small windows and shared courtyards were often occupied by members of the same family. Traditional one-story houses of Diyarbakır opened up to the streets through small doors. As people talk about the delivery of new houses and problems with registration of the buildings, there is one more important issue: lack of up-to-date cadastral maps and settlement plans. Furthermore, the structures in courtyards were not registered – this means that in the regeneration process, these areas will not be included in calculations of compensation. The fabric and style of the new houses don’t allow residents to “recreate” their traditional lifestyle, which will result in alienation.

During the days of fighting in Sur, Ahmet Davutoğlu, then prime minister, visited Sur on April 1, 2016, when a curfew had been imposed for 124 days. During his visit, he made a striking statement about the regeneration plans in the area: “This area would still need a regeneration plan even if these incidents hadn’t happened. We will build decent houses in Sur, Silopi, Nusaybin and similar regions. Diyarbakır’s houses, mosques, churches and inns under state protection will be renovated without damaging the architectural fabric of the city. We will rebuild Sur in such a way that it will be an attraction with its architecture, just like Toledo.”

PRISON-LIKE BUILDINGS IN SUR!

Today, Sur doesn’t resemble Toledo, nor does it have anything left from its old days. According to images obtained by Mezopotamya News Agency in July 2021, demolition of buildings is still underway, and renovation work continues on some historical monuments. The monochrome, uniform buildings stand out with their architectural style. The houses near the city walls open to isolated courtyards surrounded by walls, which resembles a prison.

The houses and courtyards inscribed in the UNESCO World Heritage List are gone. Courtyards with a single tree in the middle look like the outdoor spaces in F-type or S-type prisons. Window guards on every building give the feeling of a penitentiary institution. When you climb on the second floor of any house, you can easily see all courtyards and indoor areas of neighboring houses. The outer walls of first floors of all houses are made of basalt-coated bricks to make them look like authentic houses of Diyarbakır while the second floors are only painted with whitewash. The size of houses and number of bedrooms are different in every block. Although the buildings are still new, the laminated floorings have already swollen. In some houses, the washbasins are coming loose and the window frames are broken.

Ferit Kahraman, local co-chair of the Chamber of Architects, says this is “the materialization of the uniformization policy.”

A CHRONOLOGY: WHAT HAPPENED IN SUR?

July 4, 2015: UNESCO added the Fortress and Hevsel Gardens in Diyarbakır to its World Heritage List. The news was announced by Ömer Çelik, Minister of Culture and Tourism.

September 6, 2015: After the first trenches and barricades appeared on the streets in September 2015, authorities declared curfew in Sur on September 6, which was lifted the next day.

September 13, 2015: A second curfew was imposed in Sur, and it lasted two days. Law enforcement launched an operation but failed to enter the neighborhoods due to trenches and barricades. Curfew restrictions were announced via the loudspeakers in mosques.

November 28, 2015: Tahir Elçi, president of Diyarbakır Bar Association, held a press conference at 11:00 am in front of a historic minaret which was damaged during clashes. In his statement he said “In this historic area, this shared space of humanity which has been home to numerous civilizations, we don’t want arms, clashes and operations. We want wars, conflicts, arms and operations to stay out of this area.” A few minutes after the conference, Elçi was shot dead. A fourth curfew was imposed for two days after the murder.

December 2, 2015: The fifth and the last curfew started in Sur, which later became the longest curfew in the world.

December 11, 2015: A 17-hour suspension of curfew was launched. Many people left the district under the supervision of elite military teams.

December 7, 2015: Shelling in Fatihpaşa under curfew caused fire in 500-year-old Kurşunlu Mosque.

January 27, 2016: Curfew was extended beyond six neighborhoods to Melikahmet Street and five other neighborhoods (Abdaldede, Alipaşa, Lalebey, Süleyman Nazif and Ziya Gökalp neighborhoods). Six days later the curfew was lifted in these areas. Lootings in homes and stores were reported.

March 9, 2016: All military operations were ended in Sur at 4:00 pm.

March 10, 2016: Adding to the destruction caused by clashes, authorities launched a new effort to take down remaining buildings in Sur. Excavators and trucks entered 6 neighborhoods where a curfew was still in place.

March 21, 2016: With a Cabinet decree, 82 percent of Sur was expropriated to reinstate “public order.”

March 29, 2016: Diyarbakır Bar Association applied to the Council of State to challenge the decree for “urgent expropriation.” Thousands of people submitted petitions to the platform created by the municipality and NGOs to object the Cabinet decree.

April 1, 2016: Prime Minister Davutoğlu visited Sur, where a curfew had been in place for 124 days. He showed a video of the regeneration plans for Sur, and said the area would be turned into a place like Toledo.

September 5, 2016: Prime Minister Binali Yıldırım arrived in Diyarbakır in the company of thousands of elite military staff and with helicopters hovering above him. He sent greetings to Sur, and said “We will protect the historical characteristics of Sur.”

December 2, 2016: The curfew in six neighborhoods in Sur entered its second year. All buildings in the area, except for a few monuments, were taken down.

April 2017: Residents of Alipaşa and Lalebey neighborhoods – although they were not under curfew – were notified that they had to evacuate their homes by the end of that month. Authorities started preparations to demolish the buildings in these neighborhoods which were already included in the urban development plans drafted many years ago.

May 23, 2017: Demolitions for “urban development project” were launched in historical neighborhoods of Alipaşa and Lalebey. Families in Alipaşa resisted the evacuation process by they were forcefully removed from the area.

May 29, 2017: In reaction to the “urban development project” in Alipaşa and Lalebey neighborhoods, NGOs, political parties, opinion leaders and ecologists came together to launch the “No Demolition in Sur” platform.

September 18, 2017: Media reported looting at Surp Giragos Armenian Church.

October 23, 2017: Council of State accepted the objections against Cabinet decrees that sanctioned “urgent expropriation” of Sur and its designation as “high-risk area.” However, the demolitions continued in Sur.

November 30, 2017: Chief Public Prosecutor of Diyarbakır rejected the criminal complaint against the demolition work in Sur, arguing that “there was no criminal act involved in the process that could require an investigation.”

(This chronology was extracted from the chronology written by Nurcan Baysal. Click here to read the full text.)

* This article has been prepared in the scope of the “New Generation of Investigative Journalism Training Project” which is implemented by Media Research Association in cooperation with ICFJ (International Centre for Journalists).