It is the Eurovision Song Contest season! As the event unfortunately can not take its usual shape due to the Coronavirus outbreak and we are denied our yearly guilty pleasure, there is time to reflect on Turkey’s Eurovision experience. Why did Turkey quit while the country was scoring high every year? As with everything, politics play a huge part.

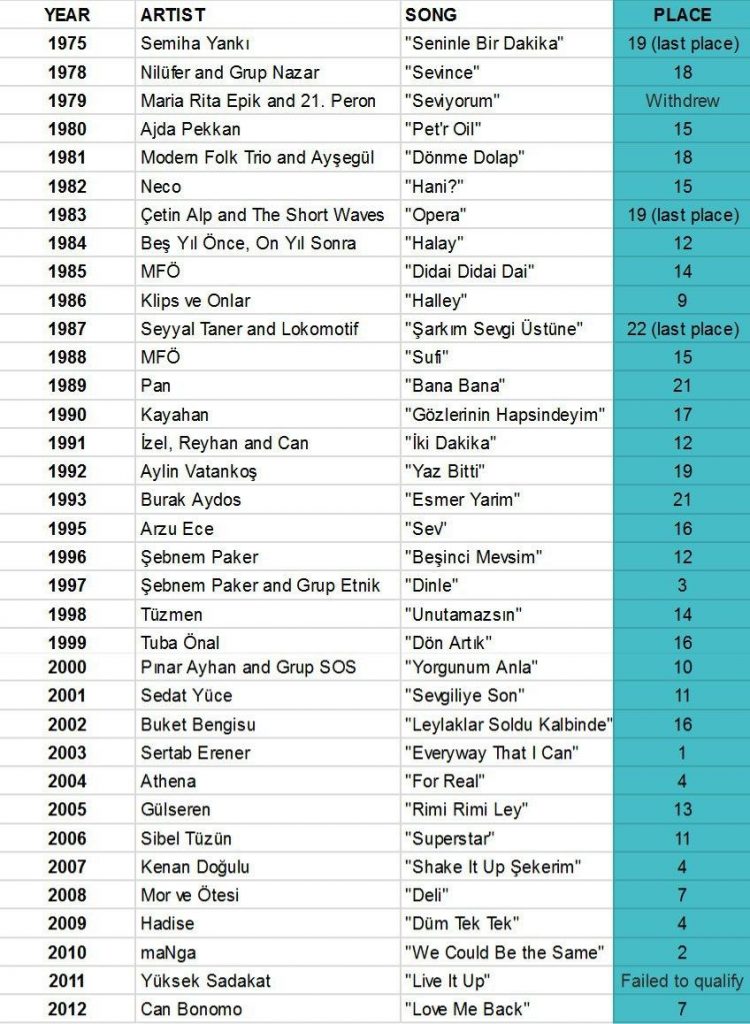

Turkey made its introduction in Eurovision in 1975 and has competed 34 times since. As anyone would tell you, the music contest was widely popular and brings a sense of nostalgia to many people today. As Orhan Pamuk mentioned in his novel A Strangeness in my Mind, by the mid-seventies many upper class households watched the show on their black-and-white television sets.[1] The electoral victory of Justice & Development Party AKP in 2002, brought to power a party that was centre-right with a conservative-democratic identity, which presented itself as being able to govern the pursuit of modernisation, democratisation, globalisation, and, most importantly here, Europeanisation. Until 2007, democratic freedoms improved as a result of wanting to accomplish EU accession criteria. Membership of the EU, and with it the solidification of Turkey’s westernness, was in reaching distance.[2]

“ARE WE EUROPEAN?”

It was in this narrative that Turkey won the Eurovision Song Contest. While unrelated to a progress in EU membership, the victory was taken as a historical moment in the history of the Turkish Republic; Erener’s victory seemed to serve as a vindication of the country’s political ambitions in Europe. Media headlines were dominated with the news the next morning. The pro-government newspaper Yeni Şafak crowned Erener the conqueror of Europe.[3] Mainstream newspaper Hürriyet columnist Hadi Uluengin wrote that she did her nation and homeland a favour.[4] Writer and journalist Oktay Ekşi seemed to ask the question on everybody's mind: ‘Are we European?’ (‘Avrupalı mıyız?’) Ekşi concludes:

“Sertab Erener dId not just wIn a musIc competItIon. She turned a new page for the TurkIsh people. [She] (…) has gIven us the IdentIty papers to enter the European UnIon, somethIng we have not been able to achIeve In our forty years of efforts, or more precIsely, In the last two hundred years.”[5]

Politically the victory was also celebrated. Erener got congratulatory phone calls from (then) Prime Minister Erdoğan and other members of the government. Minister of Foreign Affairs Abdullah Gül claimed the victory as the government’s as it provided the prestige for a victory. Erdoğan reportedly claimed that “this result will speed up Turkey’s EU process.”[6]

EU REFORM FATIGUE

With the blessing of the EU leaders, accession negotiations for Turkey started in November 2005. Things did not turn out the way Turkey hoped, as domestic and external factors blocked further talks. Ongoing opposition inside the EU to Turkey’s membership undermined the credibility of the EU’s commitment.[7] Negotiations came to a halt again in December 2006. In the meantime, Turkey experienced a ‘reform fatigue’ after an intense wave of EU reforms up until 2005. Slowly but steady Europe lost its central role within the political debate, with AKP starting to lay a focus on other issues.[8] An opinion piece in the right-wing newspaper Sabah by the highly influential writer Hıncal Uluç stated that Eurovision has lost its value[9]:

“Who cares about EurovIsIon anyway. We are the only ones In the world who take It serIously.”

A CHANGE OF NARRATIVE

In the post-2007 era, independent media in Turkey suffered a blow. In short, there were three main reasons for the loss of media independence: the concentration of media ownership by pro-government companies, the breakup of unions by media owners, and government legislation that restricted critical reporting.[10] Independent media, the watchdog of a democracy and an important source for education, became restricted by the government. More specifically, the public opinion of Europe and the EU could be highly influenced through a change of direction in AKP’s foreign policy and the emphasis on a cultural connection with the regions of the old Ottoman past.[11]

PLAYING AN UNFAIR GAME

A feeling of ‘not belonging’ arose in the 2009 edition of Eurovision. As pop star Hadise would enter the stage, expectations were high as even Erdoğan wished the singer good luck on live television.[12]

Even though Hadise became fourth in the finals, Turkish media underlined the injustice of the system. There were complaints about countries not voting for the best performance but on a basis of good relations with other countries. It might be of importance to note here that since Azerbaijan entered the competition in 2008, Turkey has given it twelve points every year.[13] The two last years of Turkey’s Eurovision participation became increasingly tainted by the idea that Europe did not play a fair game. This sentiment was empowered by the changing of the voting system starting in 2011: national juries would now make up for fifty percent of the votes. This resulted in a historically bad result for Turkey that year. Newspaper Sabah claimed: “Let's face it, Eurovision voting is based on the countries' pre-existing convictions.” [14] 2012’s performance by Can Bonomo received similar reactions on Twitter: “It is not Eurovision, it is a geography lesson”; “As long as Iran, Iraq and Syria are not participating we have no chance in Eurovision.”[15]

EUROVISION POLITICS

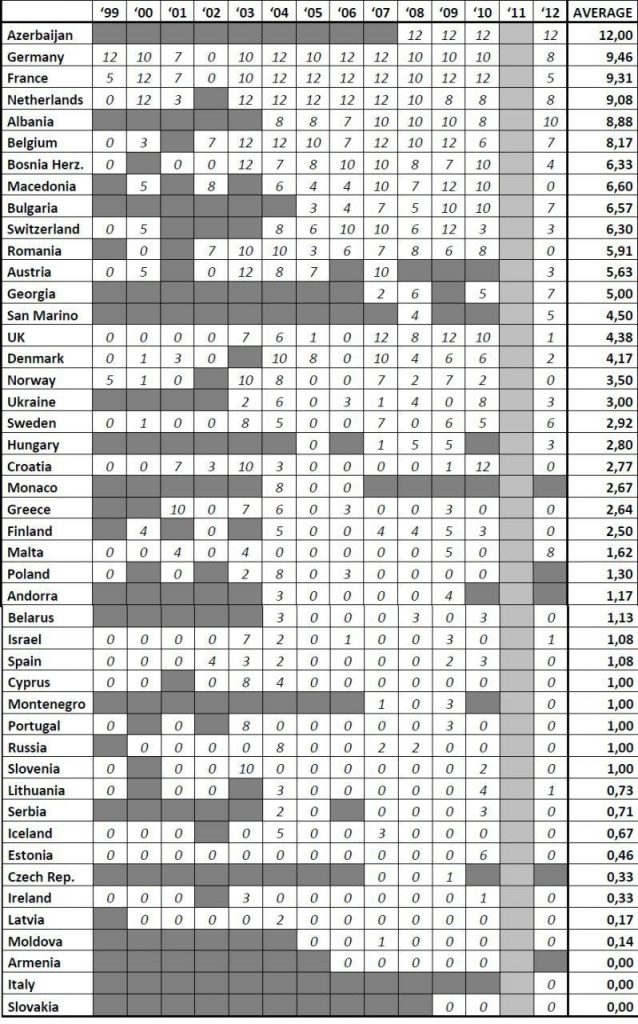

On the 12th of December 2012, state broadcaster TRT announced that Turkey would not take part in Eurovision 2013 in Sweden. The reasoning behind it were the changes and resulting injustices in the contest’s voting system.[16] A sentiment of unfairness of the voting system was not new for Turkey. Before the televoting had been introduced, the country felt disadvantaged because of its outsider position. It is true that Turkey started scoring much better after the introduction of televoting. Up until 1996, Turkey only reached the top ten once in its eighteen tries. Starting from 1997 (in which televoting became optional), this number increased to nine top ten performances out of sixteen. Here it is visible that Western European countries are more eager to vote for Turkey’s entries. Especially Germany, France, the Netherlands, Austria, and Belgium have given generous votes every year. These countries’ Turkish citizens make up their largest minority group, ranging from approximately two million in Germany to 50 thousand in Austria.  Turks residing in Europe could easily vote to support their home country. Moreover, it has happened that TRT commentators would encourage Turks living abroad to vote for Turkey. In the new voting system, a jury would decide 50 percent of all votes in order to combat “geographical favoritism.” Nonetheless, biased voting has fuelled the thought that Europe indeed did not want Turkey to be a part of it. Likewise, no substantial progress had been made in Turkey’s EU negotiations.

Turks residing in Europe could easily vote to support their home country. Moreover, it has happened that TRT commentators would encourage Turks living abroad to vote for Turkey. In the new voting system, a jury would decide 50 percent of all votes in order to combat “geographical favoritism.” Nonetheless, biased voting has fuelled the thought that Europe indeed did not want Turkey to be a part of it. Likewise, no substantial progress had been made in Turkey’s EU negotiations.

THE PIETISATION OF MEDIA

While TRT’s announcement came as a surprise, in hindsight it could be said that the withdrawal was to be expected. AKP won its third general elections in 2011, encouraging the party to continue its process of the Islamisation of society.[17] In this era, modernity was no longer synonymous to the West. Media and entertainment were not excluded in the pietisation of society, even when it came to international events. Eurovision was no exception: after the news broke that the Finnish entry will show a kiss between two women in the song ‘Marry Me’, TRT decided last minute not to broadcast the contest at all after complaints by the Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTÜK).[18] Two years later, when the Austrian drag persona Conchita Wurst won the contest. TRT chief Ibrahim Eren commented in 2018 that “someone like the bearded Austrian who wore a skirt is one of the main reasons of Ankara’s ongoing boycott against Eurovision. I have told them [EBU] on the Eurovision issue that they deviated from their values.”[19] Eurovision has been closely connected to gay culture ever since the transgender singer Dana International (Israel, 1998) won the contest. Since then it has become a site of LGBTI+ politics. The contest, known by some as the ‘gay Olympics,’ has given visibility to homo- and transsexuality in conservative areas, empowering local lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) communities.[20] The Turkish LGBT organisation Kaos-GL also took offense to the withdrawal, saying that it is an active attack on media freedom and the censorship of queer identity.[21] The decision made by TRT on the basis of values thus insinuate an 'immorality of western media,' something that no longer belongs in Erdoğan’s Turkey.

AN AWKWARD FIT

Media in Turkey changed immensely in the period from 2000 until 2012. To the Turkish public, Eurovision had gone from representing their chance of becoming European to a discriminatory organisation that wished them no good. A change in foreign affairs was tangible; as political ambitions shifted to the East, Europe was no longer a priority. This led to a drop in popularity of the music event in regard to politics and media. Eurovision started to become an awkward fit in a media landscape that was increasingly influenced by the government.